1. Contrary to conventional wisdom, in the long-run smaller companies have outperformed larger ones in generating returns.

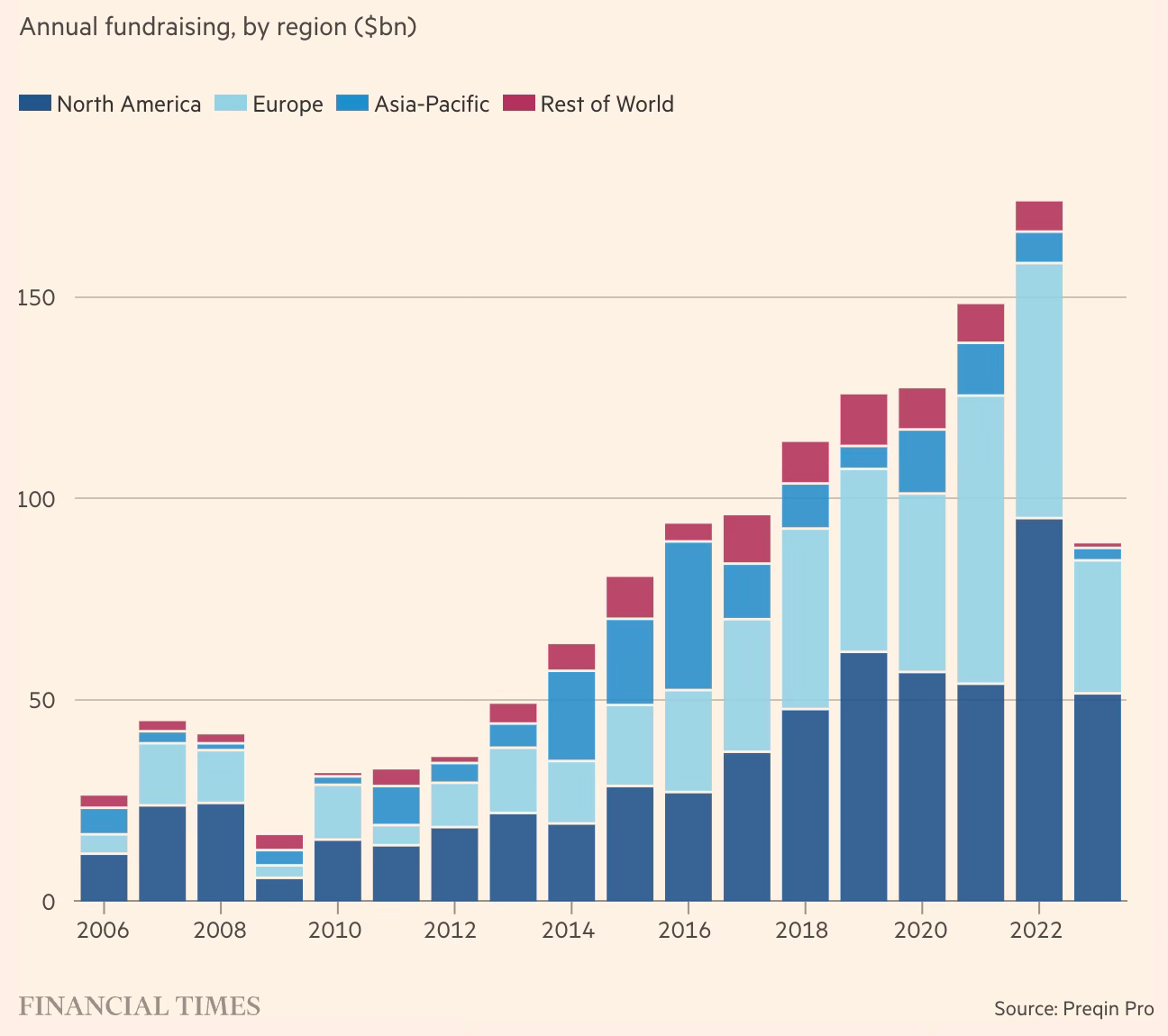

The outsize returns of small companies relative to larger peers was documented in the early 1980s using evidence from the half-century to 1975. The idea found theoretical support. Higher returns compensate investors for taking on the greater risk of backing smaller, younger companies — though that can be minimised in a diversified portfolio... Over the long run, small-cap companies have outperformed larger ones, according to the UBS Global Investment Returns yearbook. Over 43 years in 34 markets, the monthly premium relative to large companies averaged 0.21 per cent. But the premium identified in the 1980s was far bigger. It can disappear — sometimes for years at a time — after periods of strong performance. That pulls down the long-term average.

2. What constitutes physiology of great cricket batting?

A sequence of three movements that produced the longest hits. First, the shoulders and hips pulled away from each other as the batter twisted into a coiled position, like a golfer at the height of a swing. McErlain-Naylor, seated on a Zoom call, demonstrated this well enough to remind me of contrapposto, the idealised stance of ancient Greek statues of discus throwers and warriors: shoulders thrown away from the hips, chest expanded, one leg more tense than the other, the frame taut and strong. Next, the most effective batters flexed their front elbow at the top of the swing and straightened it back out as they brought the bat through their stroke. Finally, they cocked and uncocked their wrists — a final lash of momentum...James Moore, a psychologist who studies voluntary movement... told me that the brain craves certainty and likes things that flow predictably. “Economy of movement and timing enhance predictability,” he said. “With those who muscle their way through, there are more moving parts, therefore less economy of movement and less predictability.” The best-timed strokes, the most beautiful ones, are those that appear to require nothing beyond a minimal, sweet connection with the ball. “Great art,” he said, “offers no more and no less than the subject matter requires.”

3. The ramp-up in the production of iPhones from India is truly spectacular.

Apple has set a new record by exporting $10 billion worth of iPhones from India during FY24, according to data provided to the government... In terms of consumer products, this constitutes the largest-ever export of a single branded product by any company from India. iPhone exports accounted for 70 per cent of Apple’s total production in FY24. Of the three suppliers, Foxconn exported 60 per cent of its total iPhone output; Pegatron 74 per cent; and Wistron (now the Tatas) 97 per cent. Apple’s total iPhone production by its three suppliers touched $14 billion during the financial year... In FY24, the cumulative export target under the PLI scheme for the three suppliers was $7.2 billion, a target they have exceeded by 39 per cent... In future, as Apple expands capacity in India, it is expected that exports will cross 80 per cent of its total production from India. Apple is the first global value chain lead firm that has made India its home, primarily for labour-intensive manufacturing exports, rather than for the domestic market...

The total exports of mobile phones from India are expected to cross $15 billion in FY24, making Apple by far the largest contributor with nearly two-thirds of the total. The Apple ecosystem has generated nearly 150,000 new direct jobs since the launch of the PLI scheme and approximately 300,000 additional indirect jobs... While the domestic market for Apple products in general and the iPhone in particular is growing fast, the company’s revenue of Rs 49,321 crore for FY23 merely constituted 1.5 per cent of Apple’s global turnover of $383.29 billion. Its FY24, revenue is expected to increase over the previous fiscal by over 30 per cent.

4. Good primers by Shyam Saran and Shankar Acharya on the emerging situation in Myanmar where the military junta is losing control over large parts of the country's territories to the resistance forces of the ethnic minorities and the army mobilised by the opposition National League for Democracy (NLD) led by Aung Sang Suu Kyi's parallel National Unity Government (NUG). The junta has been on the back foot after the civil war broke out following its refusal to recognise the electoral verdict in 2021 won overwhelmingly by the NLD which represents the Burman majority. The junta carried out a military coup and installed itself in power, forcing the resistance from NLD and ethnic minorities.

5. The national highways monetisation program of the government of India must count as one of the great successes of PPP anywhere in the world. The NHAI has been doing monetisation through TOT bundles and Infrastructure Investment Trusts (InvIT).

The authority has so far issued 14 bundles of national highways in the TOT mode. This instrument gives highway players the right to collect toll for a specific period by paying the authority upfront cash. The valuation is arrived at through competitive bidding. After having struggled with getting bids considered fair by the authority, NHAI has awarded 10 TOT bundles to raise Rs 42,000 crore since the beginning of the asset monetisation pipeline. In InvIT, the trust which has numerous tax benefits for investors, buys the road from the authority and operates it. It distributes toll earnings in the form of return on units. NHAI has executed three rounds of offers through its InvIT, raising close to Rs 26,000 crore... In FY24, the highway authority had identified 46 national highway stretches, spanning 2,612 km for monetisation through ToTs and InvIT. It finished the financial year, meeting over 90 per cent of its target of Rs 44,000 crore... NHAI had monetised highway assets worth Rs 40,314 crore, through its three models — TOT, InvIT, and toll securitisation — for specific projects, such as the Delhi-Mumbai expressway... The National Highways Authority of India (NHAI) is looking to monetise 33 stretches of national highways during the current financial year (FY25) through its toll operate transfer (TOT) and infrastructure investment trust (InvIT)... Cumulatively, the 33 stretches, spanning 2,741 kilometres (km) earned approximately Rs 5,000 crore revenue in FY24.

6. Harish Damodaran has a brilliant article where he points to some interesting facts about Tamil Nadu, the state with the most diversified economy. This about diversification in agriculture itself.

About 45.3% of TN’s farm GVA comes from the livestock subsector, the highest for any state and way above the 30.2% all-India average. Not surprisingly, TN is home to India’s largest private dairy company (Hatsun Agro Product), broiler enterprise (Suguna Foods), egg processor (SKM Group) and also “egg capital” (Namakkal).

And this about the nature of its industrialisation

TN has just a handful of large business houses with annual revenues in excess of Rs 15,000 crore: TVS, Murugappa, MRF, Amalgamations and Apollo Hospitals. Even they are not in the league of Tata, Reliance, Aditya Birla, Adani, Mahindra, JSW, Vedanta, Bharti, Infosys, HCL or Wipro, as far as turnover goes. TN’s economic transformation has been brought about not by so-called Big Capital as much as medium-scale businesses with turnover range from Rs 100 crore to Rs 5,000 crore (some, like Hatsun and Suguna, have graduated to the next Rs 5,000-10,000 crore level). Its industrialisation has also been more spread out and decentralised, via the development of clusters. Some of the clusters – agglomerations of firms specialising in particular industries – are well known: Tirupur for cotton knitwear (the units there clocked exports of Rs 34,350 crore and Rs 27,000 crore of domestic sales in 2022-23); Coimbatore for spinning mills and engineering goods (from castings, textile machinery and auto components to pumpsets and wet grinders); Sivakasi for safety matches, fire crackers and printing; Salem, Erode, Karur and Somanur for powerlooms and home textiles; and Vaniyambadi, Ambur and Ranipet for leather.Many cluster towns are hubs for multiple industries. Thus, Karur has powerlooms, bus body builders and even makers of mosquito and fishing nets (one of them, V.K.A. Polymers, is a major exporter of insecticide-treated bed nets). Dindigul has spinning mills and leather tanneries. Namakkal is as famous for layer poultry farms as its large lorry fleet/bulk cargo logistics operators and tapioca-based sago (sabudana) factories. Salem has powerlooms and tapioca starch-cum-sago producers, while Erode is a textile and “turmeric city”. In contrast to them are the more sub-specialised clusters. Chatrapatti, in Virudhunagar district’s Rajapalayam taluka, is “bandage city” not for nothing: It is a manufacturing centre for bandages, gauze pads/rolls/swabs and other surgical cotton products and woven dressings.Tiruchengode is India’s “borewell rigs capital”. The borewell drilling services contractors of this town near Namakkal take their truck-mounted rigs all over the country to dig up to 1,400 feet. Dhalavaipuram, hardly 10 km from Rajapalayam, specialises in production of nighties and ladies innerwear, just as Natham, next to Dindigul, does in low-priced men’s formal shirts. Most of these clusters have come up in small urban/peri-urban centres, providing employment to people from surrounding villages who may otherwise have migrated to big cities for work. They have, moreover, created diversification options outside of agriculture, reducing the proportion of TN’s workforce dependent on farming.TN’s early industrialists were mainly Nattukottai Chettiars and Brahmins... Prominent among them were Annamalai Chettiar (the M.A. Chidambaram and Chettinad groups descended from him), A.M.M. Murugappa Chettiar (Murugappa Group), Karumuttu Thiagaraja Chettiar (textile magnate) and Alagappa Chettiar (textiles, insurance, hotels and education). The big Tamil Brahmin-owned houses included TVS, TTK, Amalgamations, Seshasayee, Rane, India Cements, Sanmar, Enfield India, Standard Motors and Shriram. A more recent name is the business software solutions company Zoho Corporation of Sridhar Vembu. The drivers of TN’s more recent decentralised industrialisation have, however, been entrepreneurs from more ordinary peasant stock and provincial mercantile castes...

The promoters of Suguna Foods, CRI Pumps, Elgi Equipment and Lakshmi Machine Works, too, are from Kammavar Naidus. The cluster capitalists of Tirupur, Erode, Salem, Namakkal, Karur and Dindigul are mainly Kongu Vellalar or Gounders... Sivasaki’s fireworks, match and printing industries have been built largely by Nadars. But this belt in southern TN – also covering Virudhunagar, Srivilliputhur, Watrap and Rajapalayam – has produced entrepreneurs from other communities as well: Raju (Ramco Group and Adyar Ananda Bhavan) and Udayar (Pothys). Many from here have also gone on to create successful product brands: Hatsun (‘Arun’ ice-cream and ‘Arokya’ milk), V.V.V. & Sons (‘Idhayam’ sesame oil) and Kaleesuwari Refinery (‘Gold Winner’ sunflower oil)... Christians (MRF, Johnson Lifts and Aachi Masala Foods) and Muslims (Farida Group)... CavinKare’s C.K. Ranganathan, a Mudaliar, was selling ‘Chik’ shampoo (taken from his father Chinni Krishnan’s name) in single-use sachets well before the likes of Hindustan Unilever latched on to the idea.

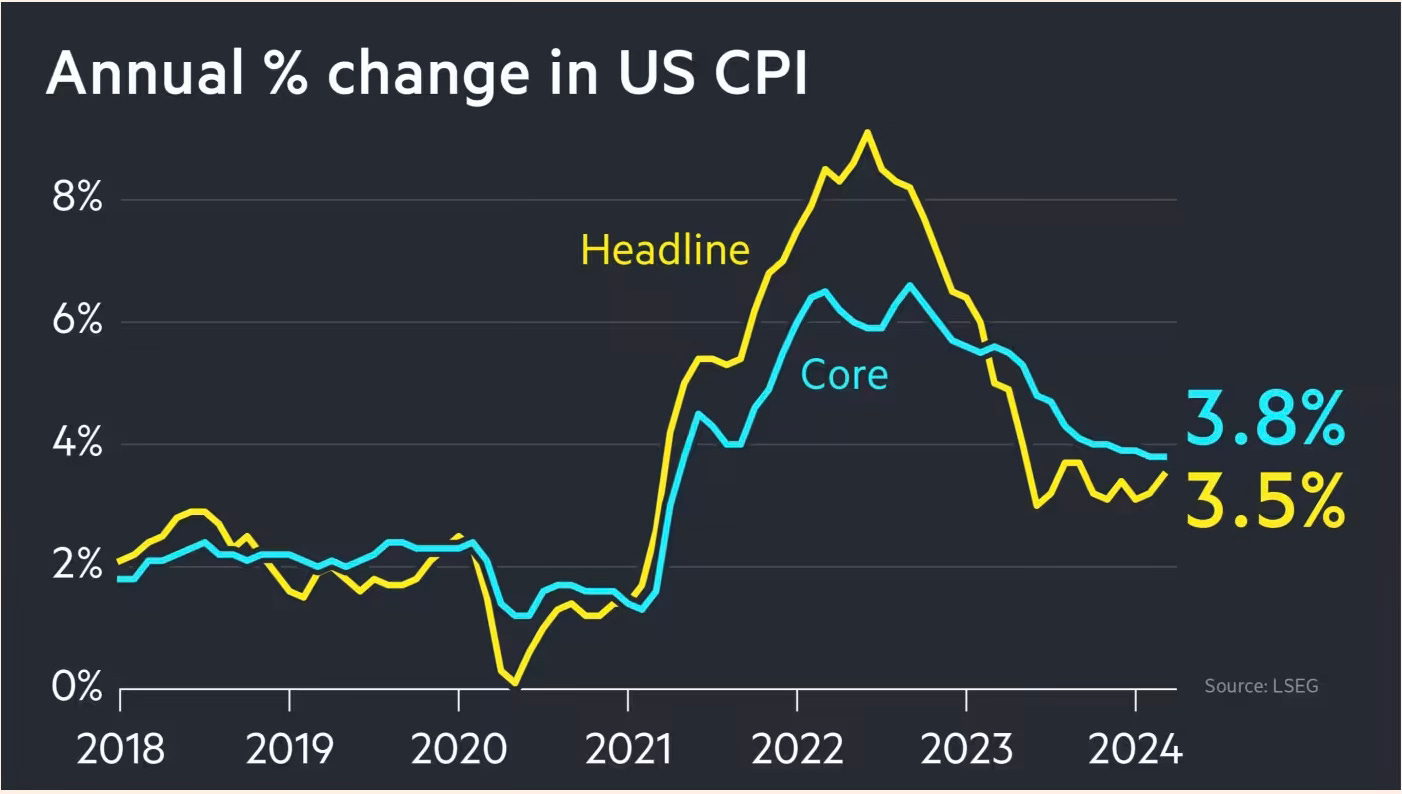

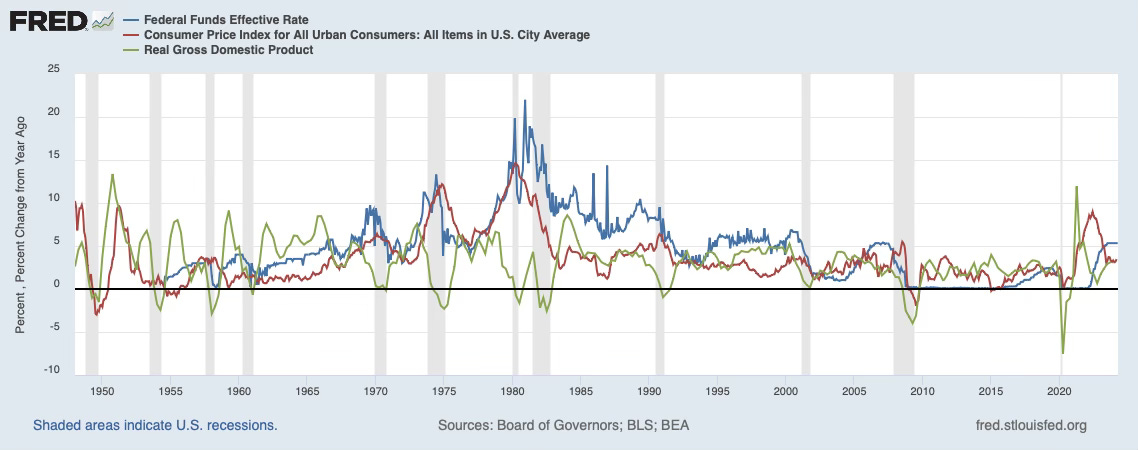

7. One line of thinking about the impact of high-interest rates on the US economy is that it may be responsible for sustained economic growth.

The jump in benchmark rates from 0% to over 5% is providing Americans with a significant stream of income from their bond investments and savings accounts for the first time in two decades. “The reality is people have more money,” says Kevin Muir, a former derivatives trader at RBC Capital Markets who now writes an investing newsletter called The MacroTourist. These people — and companies — are in turn spending a big enough chunk of that new-found cash, the theory goes, to drive up demand and goose growth.

8. Andrew Haldane has some home truth about inflation forecasting within central banks.

In the early years of inflation targeting in the UK, the then head of forecasting at the Bank of England entered my room clutching a piece of paper. On it were two lines: the inflation forecast produced painstakingly by his team over the preceding weeks, and an alternative inflation projection hand-drawn in pencil by the then governor. Only the latter “forecast” ever saw the light of day... Former central bank governor Mervyn King used to observe that the probability of forecasts proving correct was almost precisely zero. (Ironically, this is one of the few BoE forecasts ever made that turned out to be accurate.)..Economic models bring rigour to policy. Unfortunately, they also bring mortis. Even models at the frontier are always at least one step behind real-world events: from the global financial crisis (when most were found to take no meaningful account of the financial sector) to the Covid-19 and cost of living crises (when most were found to have no well-developed sectoral supply side). In these instances, models served to unhelpfully blinker policymakers to events playing out before their eyes, but not embedded in their models. This led to them first missing these crises, and then responding too slowly. Those models can also be gamed in ways that impose too few constraints on policy. In my experience, many policymakers produced their economic forecasts by working backwards from their preferred stance. This is an inversion of the way inflation targeting was meant to operate.

9. It's not UK, but Sweden that has the deepest capital markets in Europe.

At a time when the UK and many other European countries are struggling to attract initial public offerings and suffering from falling trading volumes, Sweden stands out for having, relative to its size, thriving capital markets that are backed by legions of investors and which are even tempting foreign companies to list... Over the past 10 years, 501 companies have listed in Sweden, more than the total number of IPOs in France, Germany, the Netherlands and Spain combined, according to Dealogic data. The UK is top with 765 listings... the Nordic country has been highly successful at encouraging smaller domestic businesses to stay at home, encouraged by the depth of its stock market... Around 90 per cent of listings are valued at less than $1bn... A key driver has been the country’s investment culture.

Consider the preference for equity investment among insurers.

Among larger investors, Swedish pension funds have long owned domestic equities. The country’s four biggest retirement schemes have roughly maintained or increased their holdings of domestic equities in recent years. In the UK, in contrast, domestic equity holdings among pension funds have plunged to about 4 per cent. Meanwhile, Swedish insurance companies have the highest holdings of stocks in the EU.

Swedish households are the most avid retail investors in Europe.

Retail investors are also big buyers of Swedish stocks, helped by a wealth of reforms in recent decades. Compared with the rest of Europe, Swedish households hold among the highest proportion of their investments in listed companies and among the lowest in bank deposit holdings, while financial literacy is greater than in Germany, France or Spain. In 1984, the government introduced Allemansspar, a product enabling ordinary Swedes to invest in stock markets. By 1990 there were already 1.7mn of these accounts, helping drive the launch of domestically focused small and mid-cap funds. Such funds arrived “10-to-20 years before any other country did anything similar, at least in Europe”... Rule changes in the 1990s allowed people to invest 2.5 per cent of the amount they allocate to their pensions into funds of their choice, supported by a public information campaign. And in 2012 the state introduced investment savings accounts called ISKs that allow individuals to invest without needing to report their holdings or worry about capital gains or dividend tax. Instead, the total value of the account is taxed — and in 2024 that was at a level of about 1 per cent... German investors have historically favoured bonds over stocks, making equity raising more challenging.

Sweden’s system appears to have translated into stock market returns. Its main index has gained 85 per cent over the past decade, while the Euro Stoxx 600 index has risen 49 per cent and London’s FTSE 100 just 17 per cent. That, too, is helping persuade Swedish small and mid-sized companies to stay at home.

10. Chinese State Owned Enterprises (SOEs) are doing better than the broader stock market index among Chinese stocks, mirroring trends in India too.

11. Good read in Business Standard on the struggles facing the apprentice system in India, where just 1% of work force entrants are apprentices.